To help the monarch recover back to historic levels, state fish and wildlife agencies along with public and private partners need to work together to continue taking actions across the monarch’s western range. The Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies developed a 50-year Western Monarch Conservation Plan to guide conservation efforts. Learn more about the actions you can take to preserve the monarch migration, support monarch health, ameliorate threats, and contribute data that guides recovery efforts.

Monarchs complete a fascinating, annual, multi-generational migration, returning to the same overwintering sites each fall and staying there through the winter until the next breeding season.

Monarchs use a variety of different habitats to complete their lifecycle, including patches of milkweed for breeding, nectar plants for migration, and coastal groves of trees for overwintering.

This approach is not currently recommended by conservation experts because of the potential impacts it may have on the health and natural distribution of the wild monarch population.

The WAFWA Western Monarch Conservation Plan outlines the multiple interacting factors that are thought to have caused the dramatic, recent fluctuations in the western monarch population.

The western monarch butterfly population has declined significantly in the past 30 years, from millions to a few thousand. Notably, in 2018 the number of overwintering individuals counted by the Western Monarch Count- an annual population census- dropped below 30,000. This number is significant because it is the modelled quasi-extinction threshold, the level at which extinction becomes highly likely within the next 20 years. However, the long-term downward trend can be somewhat obscured by year-to-year variation. This is because, like other butterfly populations, monarch’s numbers fluctuate annually. Insects generally have high reproductive rates that help them bounce back from years with adverse conditions. This bounciness means that they can have years of low number followed by higher years. For example, the low of 1,900 overwintering monarchs in 2020 appears to have been followed by a bounce back up to over 200,000. While this one-year increase offers hope, the overall downward remains trend concerning as does the fact that the threats to the monarch have not been adequately addressed.

Keep Monarchs Migrating

Migration is an important component of the monarch butterfly’s life history

Monarchs complete a fascinating annual multi-generational migration, returning to the same overwintering sites each fall and staying there through the winter until the next breeding season. Despite intensive study, the monarch’s migration mechanisms remain a mystery that captures the imagination. Although flying hundreds to thousands of miles exacts a high physiological cost, migration is an important adaptation that helps to keep monarch populations healthy. By moving to new locations monarchs can find new patches of milkweed, increasing their offspring’s survival potential (Flockhart et al. 2012). Migration also helps the butterflies break the parasite- or disease-host cycle (Altizer et al. 2015; Bartel et al. 2011; Satterfield et al. 2016). By distributing the population over a large geographic area, monarchs spread out risks posed by predators or other impacts such as habitat destruction from high intensity wildfire. Migration also connects the eastern and western populations. Movement between populations may also help the butterfly maintain genetic diversity and adaptive capacity (Freedman et al. 2021).

WAFWA’s Western Monarch Conservation Plan provides guidance for protecting the habitat monarchs need to complete their migration, breeding, and overwintering stages throughout their western range. Some actions include planting native milkweed species and insecticide-free nectar plants.

Native milkweed keeps monarchs healthy

Monarchs coevolved with native milkweed species that die back in the winter. Because their breeding sites senesce every fall, western butterflies flock en masse to groves of trees along the California coast to overwinter in reproductive diapause – a state in which they don’t breed for an extended period of time. The overwintering groves also provide shelter and climatic regimes that benefit monarchs during winter storms and low temperatures (Pelton et al. 2016).

To support the monarch’s migratory behavior plant native milkweed. Avoid planting tropical milkweed, which is introduced and does not die back in the winter. As an evergreen, tropical milkweed allows the protozoan parasite Ophryocyctis elektroskirra (Oe) to build up to unnatural levels, causing wing deformation or even death for exposed monarchs.

Nectar plants support migration and overwintering

Adult monarchs only consume nectar, which contains sugar and other nutrients. Nectar acts as fuel that allows monarchs to migrate long distances as well as to survive the winter period by building fat stores (Chapin and Wells 1982). Planting insecticide-free nectar plants that bloom during the periods of time when monarchs are present in your area will provide critical resources to assist them on their incredible journey.

For more information, please see:

• Xerces Society Monarch Plant List

• Monarch Joint Venture Tropical Milkweed Factsheet

Create and protect habitats that benefit monarchs

Protecting monarchs means preserving and restoring their habitats

Monarchs use a variety of different habitats to complete their lifecycle, including patches of milkweed for breeding, nectar plants for migration, and coastal groves of trees for overwintering. As a far-ranging migratory species, monarchs need high-quality breeding locations and nectar resources distributed across the landscape. WAFWA’s Western Monarch Conservation Plan promotes numerous strategies for enhancing habitats that support monarchs while highlighting that a habitat-based approach is the most appropriate for helping to conserve monarchs over the long-term.

Plant regionally appropriate milkweed species

As their obligate host plant, monarchs depend on milkweed (Asclepias) to reproduce. When creating habitat, include regionally appropriate, native milkweeds. Avoid planting nonnative perennial milkweed species such as tropical milkweed (A. currasavica) and balloon plant (Gomphocarpus physocarpa); these species don’t die back in the winter thereby exposing monarchs to higher levels of disease and potentially inducing breeding during the winter period (James et al. 2021). For more information on issues associated with non-native milkweed species, see the Monarch Joint Venture Tropical Milkweed Factsheet.

Create nectar-rich habitat

Nectar is the primary food source of adult monarchs. Nectar creates fat stores that allow monarchs to migrate long distances as well as to survive the winter period (Chapin and Wells 1982). Nectar resources are particularly important during the overwintering period as well as the fall migration, when flowering plants tend to be in short supply. Plant regionally appropriate native insecticide-free nectar plants, focusing on periods when monarchs occur in your area. For help selecting nectar plant species, see the Xerces Monarch Nectar Plant Guides.

Protect, improve management of, and restore monarch overwintering habitat

The overwintering period is a vulnerable time in the monarchs’ life cycle (Pelton et al. 2016). Western monarchs overwintering habitat predominantly occurs along the California coast, historically reaching from Baja California to Mendocino county. Many overwintering sites are publicly owned but have not been managed to protect the conditions that support the microhabitat conditions favored by monarchs. Advocating for better protections and management within the groves may contribute to their protection. If volunteer opportunities are available, you can get directly involved in habitat restoration activities. If you live near an overwintering site, select nectar plants instead of milkweed for your garden. Focus on plants that bloom during the monarch’s overwintering period (mid-September through mid-March). To identify existing overwintering habitat, consult the map on the Western Monarch Count website.

Protect monarch habitat from insecticides

It’s important to ensure that the milkweed and nectar species you plant are insecticide pesticide-free so that you don’t inadvertently harm monarchs by creating an ecological trap (providing a deadly food source instead of a beneficial one). A 2020 study found an average of 9 different types of pesticides in milkweed leaves (Halsch et al. 2020), including in plants purchased from nurseries. To learn more about purchasing plant materials, see the Xerces Guide to Buying Bee-safe Plants. If habitat is developed in areas with high pesticide use, try to create spatial or vegetative buffers around habitat to limit drift.

Share your habitat projects

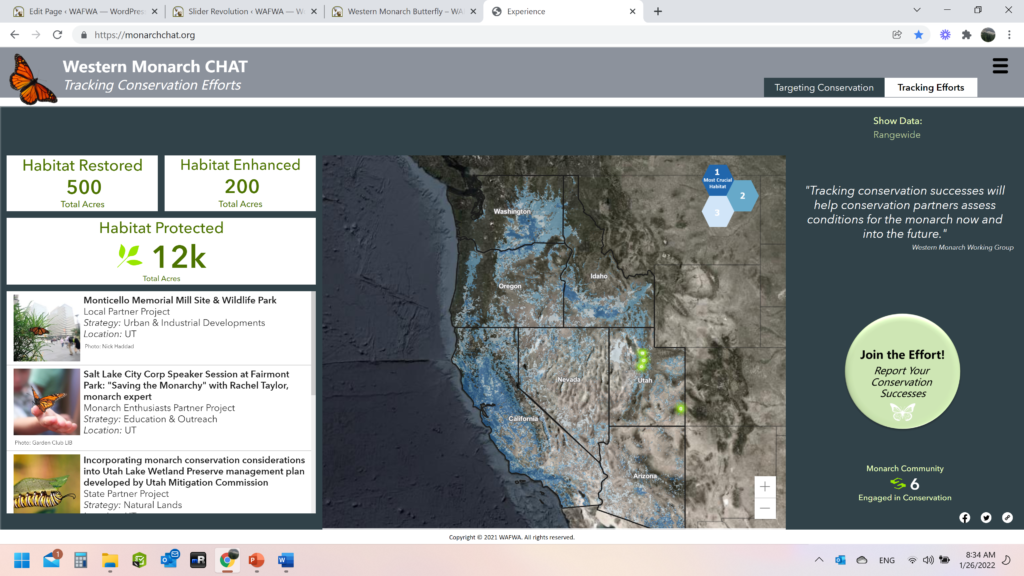

The WAFWA Monarch Plan sets a sort-term goal of creating at least 50,000 additional acres of monarch habitat. Help us track efforts around the west toward meeting this goal by adding your habitat project to our Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool (CHAT).

Become a monarch scientist!

One of the many ways to get involved in monarch conservation is to help community science programs collect data on monarchs and their habitat.

What is community science?

Community science (sometimes referred to as citizen science) is when members of the public help to collect data for local, regional, or national scientific research studies. Through the volunteer efforts of community members, scientists can often reach broader audiences (both geographically and demographically), collecting data that would otherwise be too costly or labor-intensive to gather.

We can’t do it without you!

Community science has played a critical role in the understanding of monarch biology and migration; currently, local, regional, and national community science efforts are underway to report locations of monarch butterflies, identify locations where monarch habitat is present (i.e., milkweed and/or nectar sources), understand patterns of disease and parasites (Oberhauser et al. 2012), and even tag monarchs so their migration patterns can be tracked (James et al. 2018). We rely on data collected through the Xerces Society’s decades-long Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count community science effort to track the size and status of the western monarch population (Schultz et al. 2017). Similarly, much of what we currently know about the migration patterns of the western population, and how the western population is connected to the eastern population, has been learned through community science tagging efforts of Southwest Monarch Study and other organizations.

The importance of community science is highlighted in WAFWA’s Western Monarch Conservation Plan, which identified a number of conservation Strategies and Actions related to community science efforts. Data from community science efforts have also been used by Xerces and other groups to develop key best management practices (BMPs) for landowners and land management agencies.

What community science program is right for you?

A number of monarch related community science opportunities are available at a range of commitment levels, however, please note that some states may have laws prohibiting certain activities or require permits. Ask the organization or leader of the community science project if their activities are allowed and permitted in your area.

- Assist WAFWA in tracking progress towards our Monarch Conservation Plan goals by uploading your habitat projects or educational activities into our Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool (CHAT).

- Help identify important breeding areas throughout the western US, by uploading your milkweed sightings to the Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper or take on more in-depth monitoring by adopting one of the Integrated Monarch Monitoring Program’s habitat plots.

- Participate in Project Monarch Health to help us understand how Oe impacts monarch health.

- Track monarch survival in your yard through Monarch Larval Monitoring Project.

- Contribute to the annual census of the overwintering population in California by participating in the Western Monarch Thanksgiving and New Year’s Counts.

For more community science projects, check out Monarch Joint Venture’s list: https://monarchjointventure.org/get-involved/study-monarchs-community-science-opportunities. Additional opportunities may be available at your local or state level, for example, your state may have a local conservation group such as the Arizona Monarch Collaborative and the Utah Pollinator Pursuit. Your local city may be participating in conservation efforts such as the Mayor’s Monarch Pledge, so check with your city, state, or local non-profit organizations for additional opportunities.

Keep western monarchs wild

Captive rearing by the public is not a viable conservation strategy

As western monarchs continue to experience steep decline, the question of captive rearing has been raised as a potential solution to amplify the population. This approach is not currently recommended by conservation experts because of the potential impacts it may have on the health and natural distribution of the wild monarch population. Currently WAFWA’s Western Monarch Conservation Plan does not include captive rearing as a conservation strategy.

Captive rearing increases risks to monarchs

Captive rearing poses the risk of transmitting disease between caterpillars raised in higher densities than they would occur in the wild using materials that may have accumulated parasites and pathogens (Altizer and de Roode 2010) . While disease and predation are natural parts of the monarch life cycle, it is possible to unintentionally infect multiple generations of caterpillars through the repeated use of rearing containers and materials. Infected individuals released into the wild may increase the incidence of disease in the wild population and cause lower survival and migration success (Bradley and Altizer 2005).

The loss of genetic diversity is a concerning impact of releasing captive-bred individuals into the wild, and even slight adaptations to captivity can be inherited by later generations (Willoughby and Christie 2018) . Non-natural rearing conditions can influence monarchs’ wing color and shape, which may have consequences for breeding and migration success (Davis, Smith, Ballew 2020).

Check whether captive rearing is allowed in your state

Depending on where you live, handling monarch butterflies for any purpose may be limited. Wildlife agencies in the states that comprise the core of the western range have varying legal authority to manage native insect species, including monarch butterflies. Before attempting to collect wild monarchs, check with your state and local wildlife agencies for information and resources on management authority.

Get involved in other actions that benefit monarchs

The WAFWA Western Monarch Conservation Plan emphasizes the importance of available native habitat and encourages efforts that increase native milkweed and nectar resources on the landscape as well as in urban gardens and landscaping. Your support of actions to preserve and restore habitat is essential to provide a safer landscape for monarch butterflies to recover their numbers (Oberhauser et al. 2016). The Monarch Plan also recognizes the important contributions community scientists have made to monarch conservation. You can also provide data used by Fish and Wildlife agencies by participating in community science initiatives.

For more information, please see:

• “Joint Statement Regarding Captive Breeding and Releasing of Monarchs.” The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

• “Rearing Monarchs: Why or Why Not?” Monarch Joint Venture.

• “Monarch Butterfly.” California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

References

Altizer, S., Hobson, K.A., Davis, A.K., De Roode, J.C. and Wassenaar, L.I., 2015. Do healthy monarchs migrate farther? Tracking natal origins of parasitized vs. uninfected monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico. PloS one, 10(11), p.e0141371.

Altizer, Sonia, and Jaap De Roode. “When Butterflies Get Bugs: The ABCs of Lepidopteran Disease.” American Butterflies, 2010.

Bartel, R.A., Oberhauser, K.S., De Roode, J.C. and Altizer, S.M., 2011. Monarch butterfly migration and parasite transmission in eastern North America. Ecology, 92(2), pp.342-351.

Bradley, Catherine A., and Sonia Altizer. “Parasites Hinder Monarch Butterfly Flight: Implications for Disease Spread in Migratory Hosts.” Ecology Letters, vol. 8, no. 3, 2005, pp. 290–300.

Chaplin, S.B. and Wells, P.H., 1982. Energy reserves and metabolic expenditures of monarch butterflies overwintering in southern California. Ecological Entomology, 7(3), pp.249-256.

Davis, Andrew K., et al. “A Poor Substitute for the Real Thing: Captive-Reared Monarch Butterflies Are Weaker, Paler and Have Less Elongated Wings than Wild Migrants.” Biology Letters, vol. 16, no. 4, 2020, p. 20190922.

Freedman, M.G., de Roode, J.C., Forister, M.L., Kronforst, M.R., Pierce, A.A., Schultz, C.B., Taylor, O.R. and Crone, E.E., 2021. Are eastern and western monarch butterflies distinct populations? A review of evidence for ecological, phenotypic, and genetic differentiation and implications for conservation. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(7), p.e432.

Halsch, C.A., Code, A., Hoyle, S.M., Fordyce, J.A., Baert, N. and Forister, M.L., 2020. Pesticide contamination of milkweeds across the agricultural, urban, and open spaces of low-elevation northern California. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8: 162.

James, D.G. and Kappen, L., 2021. Further insights on the migration biology of monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) from the Pacific Northwest. Insects, 12(2), p.161. Pelton, E., S. Jepsen, C. Schultz, C. Fallon and S.H. Black. 2016. State of the Monarch Butterfly Overwintering Sites in California. 40+vi pp. Portland, OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

James, D. G., T. S. James, L. Seymour, L. Kappen, T. Russell, B. Harryman, and C. Bly. 2018. Citizen scientist tagging reveals destinations of migrating monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus (L.) from the Pacific Northwest. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 72(2):127–144.

Oberhauser, K. S. 2012. Tachinid flies and monarch butterflies: citizen scientists document parasitism patterns over broad spatial and temporal scales. American Entomologist 58:19–22.

Oberhauser, Karen, et al. “A Trans‐National Monarch Butterfly Population Model and Implications for Regional Conservation Priorities.” Ecological Entomology, vol. 42, no. 1, 2016, pp. 51–60.

Pelton, E., S. Jepsen, C. Schultz, C. Fallon and S.H. Black. 2016. State of the Monarch Butterfly Overwintering Sites in California. 40+vi pp. Portland, OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Pelton, Emma, and Authors., Emma Pelton Senior Endangered Species Conservation Biologist Western Monarch Lead . “Keep Monarchs Wild: Why Captive Rearing Isn’t the Way to Help Monarchs.”

Satterfield, D.A., Villablanca, F.X., Maerz, J.C. and Altizer, S., 2016. Migratory monarchs wintering in California experience low infection risk compared to monarchs breeding year-round on non-native milkweed. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 56(2), pp.343-352.

Schultz, C. B., L.M. Brown , E.M. Pelton, E.E. Crone. 2017. Citizen science monitoring demonstrates dramatic declines of monarch butterflies in western North America. Biological Conservation, 214: 343-346.

Willoughby, Janna R., and Mark R. Christie. “Long‐Term Demographic and Genetic Effects of Releasing Captive‐Born Individuals into the Wild.” Conservation Biology, vol. 33, no. 2, 2018, pp. 377–388.